The final three minutes underway, The Forum in Inglewood was shaking like the world was at its end. After being punched groggy to end the previous round (“virtually out on his feet,” the UPI reported), the Mexican stormed back against the visiting southpaw from Thailand, stealing the closing period. His face so beaten that he was nearly blind.

It was 1973. And for 15 rounds, Rafael Herrera followed around his challenger Venice Borkorsor, “who would walk back away and sharp shoot with strong left hands” (UPI). Not to mention headbutts aplenty. At stake was supposed to be a unification with WBA beltholder Romeo Anaya. Herrera, of Jalisco, eked out an unpopular split-decision. Twenty-two years following that seminal encounter, Mexico’s own Humberto “Chiquita” Gonzalez had himself a bristling go at the formerly known Great Western Forum with Saman Sorjaturon, from Thailand. Up from an an early knockdown to win the middle stages, Chiquita would be cudgeled into submission by the seventh round.

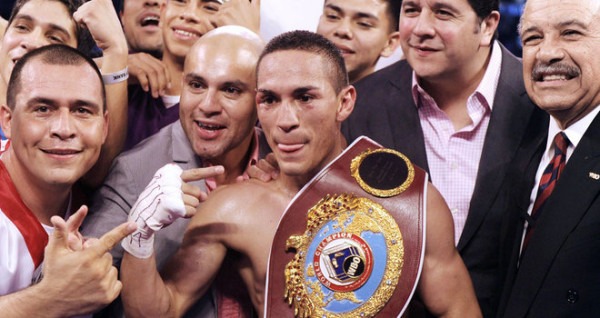

Fast-forward another 24 years, Juan Francisco Estrada (38-3, 26 KO) continues this most violent tradition alongside Srisaket Sor Rungvisai (47-4-1, 41 KO), revisiting The Forum in a rematch, slated for April 26.

Return fights have defined “El Gallo” Estrada’s career. He suffered his first loss in 2011, at the hands of former titleholder Juan Carlos Sanchez Jr., reversing the verdict that same year. A pursuit of a rematch with Roman “Chocolatito” Gonzalez, after battling at 108 pounds, then lifting two titles at flyweight-proper, forced the Mexican into HBO’s super flyweight scrum.

Return fights have defined “El Gallo” Estrada’s career. He suffered his first loss in 2011, at the hands of former titleholder Juan Carlos Sanchez Jr., reversing the verdict that same year. A pursuit of a rematch with Roman “Chocolatito” Gonzalez, after battling at 108 pounds, then lifting two titles at flyweight-proper, forced the Mexican into HBO’s super flyweight scrum.

“Life gives you second chances,” Estrada said in a recent DAZN production chronicling his rise from the wide valleys of Sonala, Mexico to boxing’s greatest heights. The 13-minute video succinctly presents not just the fighter’s life—his nicknamed bestowed upon him by a local newspaper after winning three straight amateur nationals—but the person: seven years old when his mother died from Leukemia; his aunt, who took him in as her own, would also pass away when he was 21. A story so gripping HBO last year took all of 76 seconds to tell it.

It took a British promotion in Matchroom Boxing to give Estrada a closer look. The kind of all-access look and artful rendering afforded any other pound-for-pound claimant. This month, alone, Eddie Hearn’s men published two other video features on the Mexican technician. One, a peek into training camp ahead of this weekend’s headliner on DAZN. The second, an intimate reflection from Estrada as he rewatched his clash with Rungvisai (titled “Round of the Year,” referring to tremendous twelfth round that capped off their first meeting). Simple gestures that MMA promotions have become so good at packaging, and that HBO, despite broadcasting Estrada’s last four fights, didn’t bother to. In their time with Estrada, mustering up two and a half minutes of Kieran Mulvaney sticking a camera in his face like a glorified Elie Seckbach.

Last December, Estrada stopped compatriot Victor Mendez, replacing Chocolatito, as a part of the network’s last hurrah. Picking up the pieces, it was DAZN, a streaming service, with their boots on the ground finally providing a vivid snapshot of Estrada’s upbringing—equal parts turmoil and perseverance.

“There are tests that God gives us,” Estrada says in the voice over of DAZN’s take on his subject matter. At the four-minute mark, the camera shifts to a reenactment of a young Gallito walking home from school. The hot, dry streets of a rundown neighborhood at this foreground—the town set to a Sonoran Desert. With his mother long gone, and equally lost is a father he never lived with, a nine-year-old Estrada serendipitously finds a boy no bigger than himself receiving boxing instructions from an unnamed man. Nothing to hit at but a sack hanging from a tree, Estrada received his first fistic lesson that day. The anonymous figure—uncredited for production purposes, to be sure—is in this dramatization a guiding light, perhaps even a guardian angel, who eventually introduces Estrada to his first formal trainer.

Rungvisai represents Estrada’s next heavenly challenge from above, equipped with the hitting power forged in the fires down below. Last year, the two slogged away at each other for 12 rounds. Estrada pulled away in the final frame just like Herrera decades prior. Though not enough. When the decision was turned in, and referee Jack Reiss raised the Thai champion’s hand in victory, Estrada’s countenance falling, behind him was promoter Tom Loeffler and matchmaker Sean Gibbons. The two are the best at what they do and, more interestingly, active on social media (Gibbons much more so). Even open to chat (or hell, argue) with on Twitter. The internet has made viewers today closer to the sport’s movers and shakers than ever before. Fans in the 1970s would be so lucky to pick up a news clipping with a quote from Herrera’s manager Chucho Cuate.

Rungvisai represents Estrada’s next heavenly challenge from above, equipped with the hitting power forged in the fires down below. Last year, the two slogged away at each other for 12 rounds. Estrada pulled away in the final frame just like Herrera decades prior. Though not enough. When the decision was turned in, and referee Jack Reiss raised the Thai champion’s hand in victory, Estrada’s countenance falling, behind him was promoter Tom Loeffler and matchmaker Sean Gibbons. The two are the best at what they do and, more interestingly, active on social media (Gibbons much more so). Even open to chat (or hell, argue) with on Twitter. The internet has made viewers today closer to the sport’s movers and shakers than ever before. Fans in the 1970s would be so lucky to pick up a news clipping with a quote from Herrera’s manager Chucho Cuate.

Boxing’s cultural moment is happening. Unlike most movements, not in the streets or political chambers, but in spaces as small as a cellphone screen. It’s a growing interest in boxing’s most obscure actors, spurred simply by the availability and capacity to watch them. The fight fan is no longer obstructed from boxing’s underground (and often international) fight clubs like cruiserweight and the sport’s little-weights. The World Boxing Super Series matchups, for example, were viewed on either another subscription site (FlowdTV) or more often than not for free on YouTube.

Years ago Canal 4 of Nicaragua live-streamed on the same weekend both Gonzalez’s conquest of the flyweight division (rearranging Akira Yaegashi’s face) and Estrada’s butchering of Giovani Segura. Each available legal and free from a laptop or mobile device. Similarly, in 2019, AsianBoxing.info picked up Kosei Tanaka’s last two title defenses. And, well, DAZN has the Rungvisai-Estrada superfight covered (for a price).

Following the grand arch of boxing history from sweltering big money gates at the Polo Grounds to an online subscription service, will not be without acclimation. For all its excellence, the card this weekend in Inglewood, has struggled to put people in the physical seats of a stadium so rich in a history permeated by violence. (Can you hear the 12,200, who were there when Herrera and Borkorsor tried to take off each others head, scoff in unison?) Looking forward to boxing’s new evolution, it would be wise not to forget the past and the thrill of attending a fight card, watching the drama unfold amid teeming humanity. Estrada, for one, recognizes the past, especially his own.

“Rungvisai and I know each other—I think in the rematch I need more intensity right from the beginning,” Estrada says in Matchroom’s “Round of the Year,” studying his familiar foe, from an iPad like so many will on Friday.

Revisiting historic grounds, inscribed on those walls at The Forum is Estrada’s fate: either the way of Chiquita Gonzalez, succumbing to a hellacious brand of punching or that of Herrera, the Mexican’s strained finger tips being raised, above his swollen purple eyes, victoriously.