Independence Day commemorates America’s declaration as a new nation.

While the United States isn’t as regarded in producing “pure boxing” talent like that of Cuba or other nations rich in amateur boxing pedigree, the U.S. has pumped out its fair share of superb stylists.

A pure boxer is hard to define, one of those Rashomon-like words that can mean just about anything you want it to. So let’s make clear what it’s not first. A pure boxer is not a brawler or a swarmer, it’s not a potshotter who relies on landing one big punch and this writer doesn’t like the idea that “pure boxing” has become equivalent to simply a defensive-minded fighter.

Pugilism is the tragic art of hitting and not being hit. So the men that follow have mastered the offensive side of the sport as much as they have the defensive part.

Only the retired were considered and to spread some of the limelight around, the Sugars, Ray Robinson and Leonard, have been omitted.

Happy Fourth of July.

5. Tippy Larkin

Tony Pilleteri, an Italian-American, out of Garfield, New Jersey was fittingly dubbed “The Garfield Gunner.” The surname “Larkin” was the title his older brother boxed under so Tony did too.

Friends and family called him “T.P.” so taking the name “Tippy” was also only natural.

And all natural is exactly what fight fans in attendance of Larkin’s eventual sixth-round knockout of Tommy Cross saw in 1942 when the New Jersey boy forgot to put on his trunks before stepping into the ring.

Larkin was a handsome man with a beautiful flair in an ugly sport. He won over 130 fights, losing 15 times but was never actually outboxed. He would have been a first-ballot Hall of Famer if not for one fatal flaw.

Robert F. Fernandez, Sr. comments in his book Boxing in New Jersey, 1900-1999:

“If Larkin had [Billy] Graham’s chin [who was never knocked out in 126 fights], he would have become a boxing immortal—the white Sugar Ray Robinson.”

It’s hard to find a newspaper report that doesn’t refer to Larkin as a “master-boxer.” His boxing ability was revered in like dazzling stylists Pernell Whitaker and Nicolino Locche after him.

“Tippy was… an artful dodger who could slip and slide and parry blows like none before,” Fernandez says. “He could feint an opponent out of position and make him look like a clumsy novice with his on-target counterpunches.”

In 1946, Larkin won the reestablished junior welterweight title, beating the excellent Willie Joyce (68-16-9) over a blistering 12 rounds. Larkin beat him on two other occasions as well.

From the time Larkin turned 20 in 1937 until walking away for good in 1952, he would fight 105 times, losing a decision just once—that being to the rough and tumble Hall of Famer Jack Kid Berg.

He wasn’t, however, the only brilliant boxer-puncher glorifying the stacked era of the time. Billy Graham was a superb boxer who in 1947 was being touted as likely Sugar Ray Robinson’s toughest competition.

When Larkin handed Graham a “thorough boxing lesson” (Edwardsville Intelligencer) that same year, he regained the prestige he had lost the month before when he was flattened by the blonde bomber Charley Fusari.

Of course, it wasn’t the first time and it sure wouldn’t be the last. Nine other stoppage losses mar his record.

KO losses to dynamite puncher Al Bummy Davis and Hall of Famers Lew Jenkins, Beau Jack, Ike Williams and Henry Armstong—who Larkin picked apart for an entire round before being caught straight right to the chin in Round 2—hinder the feasibly legendary career he could have had.

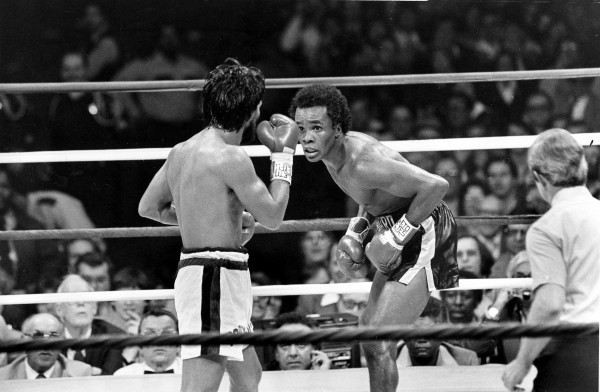

4. Ezzard Charles

Following a record 25 title defenses of his heavyweight crown, Joe Louis walked away from the sport.

Ezzard Charles took the vacant throne in 1949 after out-jabbing rival Jersey Joe Walcott to a 15-round unanimous decision. Louis did eventually come back for his own shot at Charles and the title he held with such authority.

But the “Cincinnati Cobra” did him a favor knocking the rust right off the former champion, burying the ghost of Louis over a cruel 15 rounds.

In all, he made nine defenses of his heavyweight title. “But the greatest Ezzard Charles, the lithe and dangerous fighting machine that could do it all, boxing historian Mike Casey notes, “wasn’t even a heavyweight.”

Charles’ ledger at light heavyweight is unparalleled and he was also the uncrowned king at middleweight. His consummate boxer-puncher style saw him beat a variety of opposition in a variety of ways.

Highlighting Charles’ run at 175 pounds are his wins over the legendary Archie Moore. The first was in 1946, dropping him with a left uppercut to the stomach. The second came in 1947, sending Moore to the canvas with a left dig to the liver. And finally he blasted Moore for good and a Round 8 KO in 1948.

At middleweight, Charles took on the often-avoided Charley Burley.

Charles beat him twice. First jumping in for hall of famer Ken Overlin in 1942, upsetting and outboxing Burley over 10 rounds and earning himself a 50/50 split of the purse in the rematch just 35 days later. “Charles proved his punching power on inside fighting and kept Burley mostly on the defensive,” as reported by Pennsylvania’s Huntingdon Daily News.

The “Cincinnati School Boy,” as he was called then, had yet to graduate high school.

Another pair of his rivals were Jimmy Bivins and Lloyd Marshall. The two legendary fighters took turns beating a 21-year-old Charles. Each loss, however, was brutally avenged—twice from Marshall and four times at Bivins’ expense.

3. Benny Leonard

Floyd Mayweather Jr. has assembled a glistening perfect record of 48-0. He is the king of modern day boxing, the defensive savant of his time, not always putting the sweet but surely the science in the sweet science.

For all that, as Lee Wylie, boxing analyst for The Fight City maintains: “Many of the same tactics and techniques that Floyd Mayweather uses to dominate the field today, Benny Leonard was employing even more authoritatively almost 100 years ago.”

A century ago, Benny Leonard was 19 years old. Between then and his first retirement in 1925, the “Ghetto Wizard” would fight 127 times, losing on just four occasions.

One defeat to the Hall of Famer Freddie Welsh was avenged by technical knockout in 1917. It was for the right to call himself the best lightweight in the world and Leonard nearly sent him through the ropes in the fateful Round 9 with a “volley of rights,” per the Syracuse Herald.

Another Hall of Famer in Johnny Dundee bested Leonard over six rounds a year earlier. As the champion, Leonard beat Dundee four times—thrice in 1919 alone.

The year 1919 also saw fortune favor Willie Ritchie, though, narrowly edging Leonard in an insignificant four rounder. The lightweight champion put him away in the rematch within eight rounds.

Leonard’s disqualification to all-time great welterweight Jack Britton in 1922 was his final and most bizarre loss before retiring atop the 135-pound class but even so, Leonard holds two decisive decisions over the defensive maestro Britton, overcoming a weight disadvantage in both cases.

“In an era where sluggers were at the forefront of the sport, Leonard’s highly mobile style and analytical approach breathed new life into pugilism,” Lee Wylie continued. “Leonard was a consummate tactician—the ultimate thinking man’s boxer.”

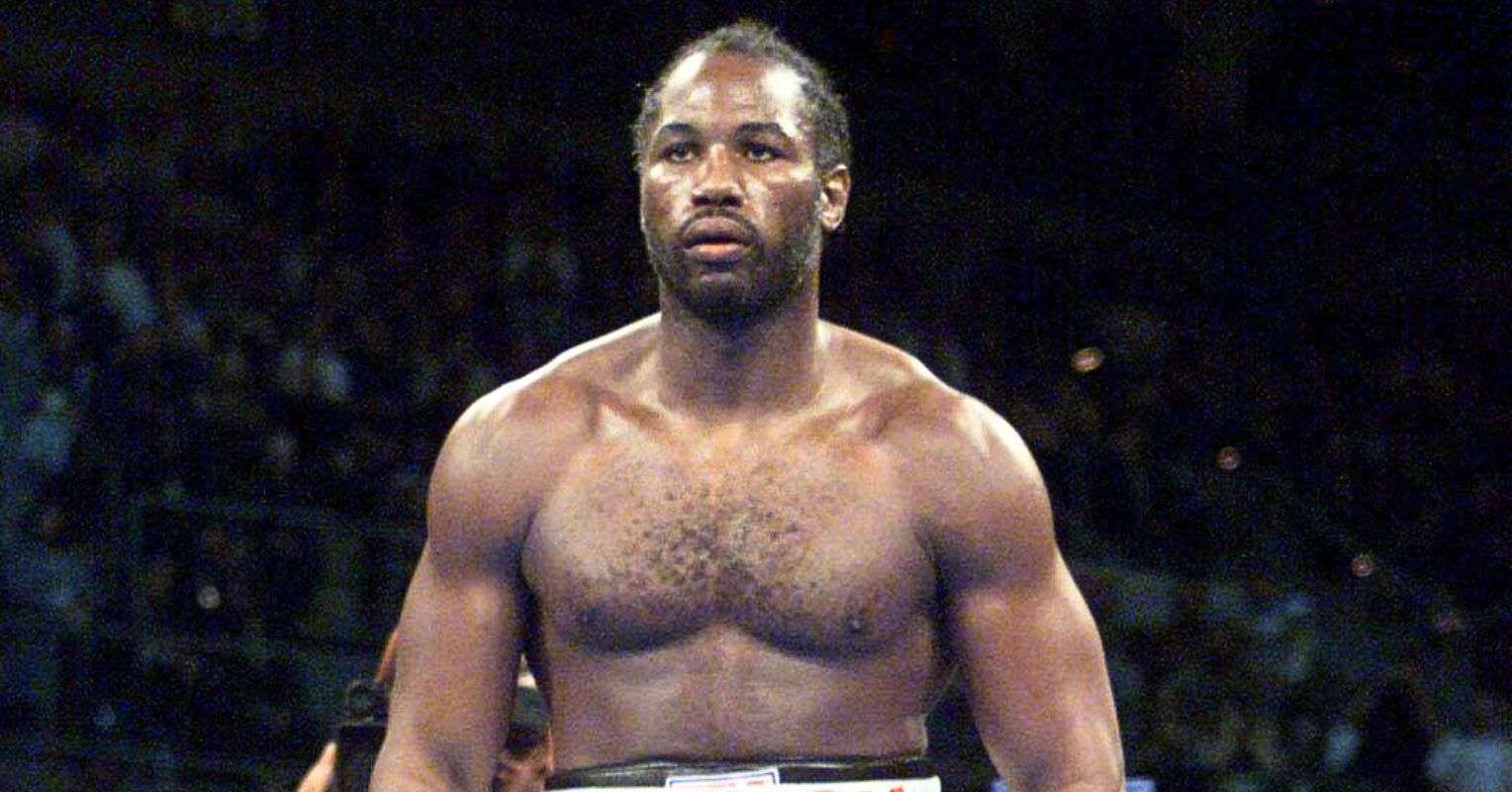

2. Pernell Whitaker

They called the man Pernell Whitaker. They called the fighter “Sweet Pea.” What he did in the ring, however, is much harder to put a name on.

“Pure boxer” would be apt. “Pure poetry” is even more fitting.

Whitaker picked up a gold medal at the 1984 Summer Olympics, helping make up the greatest national team in American history.

He debuted in the paid ranks later that year. He wouldn’t be truly “outboxed” through 42 bouts until dropping a unanimous decision against Oscar de la Hoya—nine years his younger—in 1997 and even that decision wasn’t without its controversy.

Not nearly as controversial, of course, as the egregious majority draw Whitaker walked out of the Alamodome with against one Julio Cesar Chavez in 1993—a fight he never officially won but ironically enough defines his entire career.

Chavez, the punch-god of Mexican lore, sporting an eerie record of 87-0 and already a three-weight world champion, had nothing for Whitaker that night.

Here’s how Boxing.com’s Matt McGrain saw it:

“It was a masterful performance ten pounds north of [Whitaker’s] best weight but two judges colluded to rob him once more, ludicrously ruling a majority draw.”

Once more?

Yes, it wasn’t Whitaker’s first time robbed blind of a prizefight.

The Ring called his split-decision “loss” to Jose Luis Ramirez (who promoters were keen on matching up with Chavez) in 1988 the worst decision of the entire 1980s, per BoxRec.com.

Whitaker outclassed Ramirez (again) in the return match a year later and proceeded to clean out the lightweight division, beating 135-pound champions, past or present, Greg Haugen, Freddie Pendelton, Juan Nazario and Hall of Famer Azumah Nelson.

He also lifted world titles at junior welterweight, welterweight and astonishingly even light middleweight.

1. Willie Pep

It was 1942 when 20-year-old Willie Pep challenged the murderous-punching Chalky Wright for the featherweight championship.

Boxing historian Springs Toledo, in his book The Gods of War, described the action like so:

“The young challenger sprinted out of his corner to center ring, put his dukes up… and disappeared. He spent round after round fighting like a figment of Wright’s imagination, offering only mirages in lieu of mayhem like a laughing ghost.”

Pep, nicknamed “Will o’ the Wisp”—homage to the elusive featherweight Young Griffo of the late 19th century—often disappeared in front of his opponents’ very eyes.

So, too, did he go missing from the public for the first six months of 1947 when a plane crash put him in a body caste for over four months.

He was back in the ring by June and defending the featherweight title by August.

Pep, the master-boxer, footwork unparalleled, and in turn a mosquito of the prize ring, floated about, drawing blood at will.

A master of angulation, Pep circled out and away from his onrushing opponents, waiting for them to overcommit and send back a stiff, not quite potent, straight right or left from either stance.

“To watch Willie Pep in action is to witness a dissertation on how to set up an opponent,” The Fight City’s Michael Carbert wrote.

The featherweight champion would lose just once through his first 136 fights, that being to the brutish Sammy Angott at lightweight.

Blood rival Sandy Saddler handed him the second loss of his career in 1948 but Pep won the return match, upsetting the 5-7 favorite over 15 rounds, boxing “beautifully all the way against his heavier punching opponent, bouncing in and out with his dazzling array of jabs, hooks and right crosses (Syracuse Post Standard).

In deep contrast, the next two fights between the two were marred in roughneck tactics—often cited as some of the dirtiest fights of all time. But amid the chaos, Pep still had his way with Saddler. Pumping out that maxim gun jab, sometimes five or six at a time, and scampering his feet across every inch of the canvas like his boots were on fire, Pep was ahead on the scorecards when the free-for-alls were eventually stopped.

Fighting past his prime into the 1960s and a record of 229-11-1 led one Sugar Ray Robinson to say that he admired Pep’s boxing ability more than any other fighter he’d ever seen (via The Sweet Science).

And that, among many things, should make fight fans proud to be an American this Independence Day.