Muhammad Ali: If It Wasn’t for the Struggle

Atlanta based rapper Pastor Troy once said, “If it wasn’t for the struggle cuz, you would not be hearing this.” That phrase encapsulates my view of the many op-eds and obits I’ve read since the passing of Muhammad Ali.

A few of those written pieces have used the phrase “transcending race” when talking about Ali’s legacy.

The phrase “transcending race” presents a paradox, because race is the foundation of Ali’s legacy; therefore, how could he transcend it?

To say an athlete of color transcends race feels like an erasure of said struggle or of his blackness, at the very least. A struggle that made Ali a better man and humanitarian.

By definition, the word transcend means to surpass or to be or go beyond the limits of. In the specific case of Muhammad Ali, he was said to have surpassed or to have gone beyond the limits of his race, origins and identity. On one hand (that hand not being black), I can see how that perspective could seem to be the appropriate complimentary assessment.

Conversely, that perspective casts aspersions about the rest of black people and their overall value to society. It also casts aspersion on those who hold this perspective–though I doubt anyone who feels that Ali transcended race would dare expand on that side of the perspective.

It’s apparent that Ali’s legacy meant a lot of different things to a lot of people. However, if you apply some context and nuance to the transcending race assessment, it becomes a sterilizing of the colorful history that got Ali to this point of transcendence.

This is a situational side effect when the majority of writers who cover sports–like boxing, where the participants are predominantly impoverished people of color–don’t have the same understanding of the world that people that they write about do. They get to opine and shape the narratives about people whose life experiences they couldn’t possibly understand. And don’t really want to, either.

No one ever said, “Rocky Marciano transcended race.” He didn’t need to. Neither should Ali.

As a young adult, Ali declared publicly that he wanted to redefine blackness. In the 1960’s and even today, black people perpetually struggle finding beauty and value in themselves based on society’s withstanding purview.

This is, in part, the result of multiple centuries-worth use of imagery and messaging through entertainment, news, politics and everyday life, reinforcing prejudices and stereotypes.

Even today, a well-known boxing champion recently used a picture of a chimpanzee in boxing gloves to represent a potential opponent of African descent.

If not for the struggle, what other vehicle could have possibly motivated Ali to respond so audaciously and so unapologetically to mainstream white society’s prejudices of blackness? And in particular… of his blackness?

It was the struggle that stoked the flames of passion within Ali and compelled him to speak honestly and unapologetically about who he was.

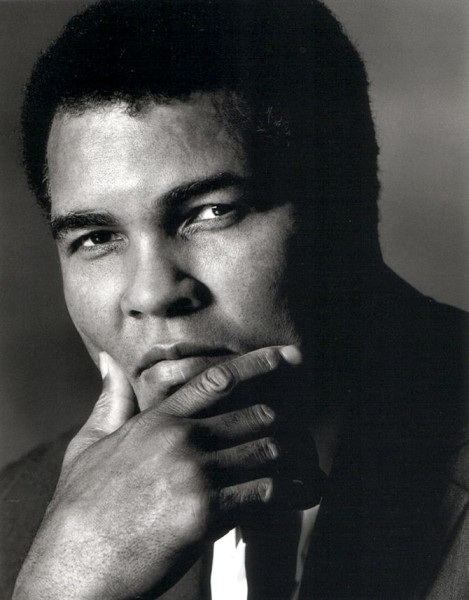

At the pinnacle of his success, Ali was despised by a large chunk of the population for his character and personality. He had the audacity to be proud of his blackness and to simultaneously refer to himself as pretty.

He changed his name and religion shortly after winning the world heavyweight title in 1964 to the chagrin of mainstream American and traditional black folk down south.

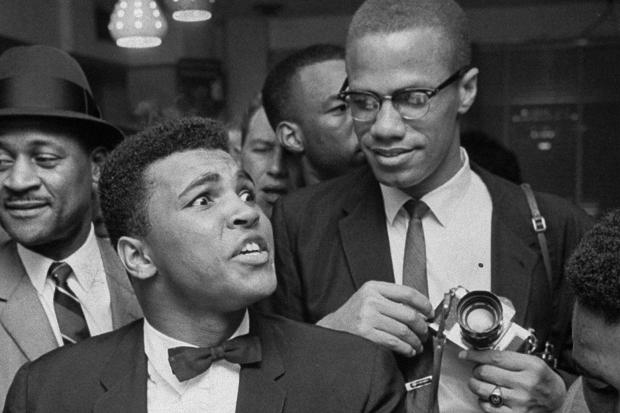

What else would drive him to the Nation of Islam-–a radical, pro-black, separatist sect of Muslim faith?

The struggle. Only the struggle.

The public hatred for Ali only amplified when he refused to go to serve in the Vietnam War as a conscientious objector, further igniting the resentment of white America. The term Draft Dodger took on a whole new popularity during this time, in reference to Ali’s protest.

He was stripped of his title and exiled from boxing for three years, paying the ultimate cost for standing up for what he believed in, at a time when it was the most unpopular thing to do.

It was the struggle that compelled Ali to denounce a war that he didn’t believe was his to fight, for a country that didn’t recognize or appreciate those of his ilk.

Photo by Bob Gomel/Getty Images

Photo by Bob Gomel/Getty Images

As Ali got older, his movements slower, his voice quieter and his focus changed to a global scale; he left the NOI converting to Sunni Islam–a move predicated by his pilgrimage to Mecca (like Malcolm X’s) and the death of Elijah Mohammed, the leader of the NOI.

After retirement, he decided he would focus on helping people through global activism and becoming an ambassador of peace.

As we memorialized Muhammad Ali all last week, the impact his legacy had on the world was on full display. We’ve seen people use his legacy as a marker of progress, despite America today seeming deeply divided on issues of race, police brutality, politics and religion at this very moment.

How far we’ve come. At least we can all use the same public restrooms; right?

I’d like to say a better measurement of progress, is if we took the version of Muhammad Ali that existed in 1964-1966 and dropped him off in present day 2016. A black athlete at the peak of his skills, defiantly telling the world how great he is? I don’t think the world would react to his personality any differently now than it did then.

Even without moving the political meter, the majority of people resented the now retired, future hall of famer, Floyd Mayweather for saying he was the best–before his domestic violence issues surfaced.

This is why the struggle or blackness is so important, because if we lose sight of it in the case of Ali, we are sanding down his rough edges to make him more palatable for mainstream white America, a concept that stands opposite to everything Ali was and everything that compelled him.

That is the struggle.

If you couldn’t tell, Muhammad Ali was black. He was so black, he was blacker than collard greens doused in hot sauce. He was blacker than deaconess wearing big-ass hats to Sunday service.

He was black way before it was an accepted term for black people. I don’t think he would want you to forget that. As long as I have a platform and voice, I’m not going to let you forget it either.

[otw_shortcode_quote border=”bordered” border_style=”bordered”]I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me–black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me. –Muhammad Ali[/otw_shortcode_quote]