CAVEAT EMPTOR: BOXING AND THE NFL

By: Bill Dwyre

Over the years, as a sports columnist for The Los Angeles Times, I received no fewer than 200 emails that asked a version of the same question: How can you write so favorably and passionately about boxing when you keep ripping the NFL and its concussions. Isn’t that two-faced, unfair? Aren’t boxers concussed as much as football players?

The emails added up to 200 guilt trips. When you have a quick and logical answer for a reader, you fire off an explanatory response and feel fine. When 200 readers seem to have a point, you squirm.

I don’t deny that I like boxing, nor that I am fascinated by its people and its never-ending story lines.

The NFL? Not so much. I always despised its control-freak approach to everything, its holier-than-thou attitude. I covered enough Super Bowls to learn how to join the media crowd, click my heels and say “Moo, Moo.”

Still, disliking a sport because of its arrogance, not to mention the pile of lies it told the City of Los Angeles for those 20 years until it let the Rams come back, is not a good enough reason to be less than open-minded.

Two recent boxing situations prompted deeper thought, and a search for my own answers.

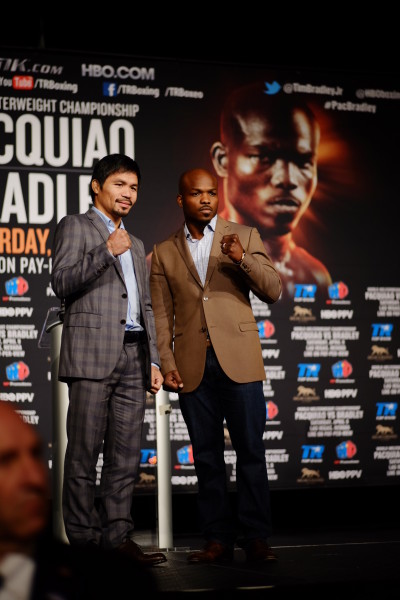

First, there was a conversation with Monica Bradley. She is the wife and manager of Tim Bradley, who will fight Manny Pacquiao April 9, in a widely anticipated match at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas.

Among the selling points of this fight are the announced last-fight retirement of Pacquiao and the newfound attractiveness of Bradley as a boxer. Part of that comes from his blood-and-guts show and victory in the 2013 Fight of the Year against Russian mayhem-maker Ruslan Provodnikov. Fans love brawls and now have the expectation that Bradley can give them one against Pacquiao, who can also brawl with the best of them on occasion.

Monica Bradley said that, because of the Provodnikov fight, she had taken her husband to several neurological clinics around the country to be sure he was all right. She also was instrumental in hiring Teddy Atlas as Bradley’s new trainer. Atlas came with the expressed intention of teaching Bradley how to get hit less. When Bradley beat Brandon Rios in his most recent fight, and his first for Atlas, that’s exactly what took place.

The concern of the Bradley camp led to more thought.

Then came the announcement that, running counter to all logic and common sense, the people who run amateur boxing in the world will put on their Olympic tournament in Rio de Janeiro this summer with its amateur fighters competing without headgear. My colleague at the Associated Press, Greg Beacham, wrote a comprehensive story about this from the team trials at Reno, as the headgear question was still being discussed. The story was about 600 words, but only three were needed in way of explanation — “more TV friendly.”

The international boxing federation (AIBA) and its president, Wu-Ching Kuo, have now officially sold out. More cut up and woozy amateurs will certainly boost the ratings. Blood sells.

Which brings us back to the pro fight game, where there is always enough blood to go around.

I pondered all this, and concluded that the only defense I have for treating it as a lesser evil than pro football is that it still is.

Of course, it is not croquet or rhythmic gymnastics. Of course it is violent and coarse. But at least it is honest in that. I have never heard a boxer say he had no idea he might get a head injury by doing this. The blood and guts and cuts and KOs and future slurring are not treated as a surprise, only an inevitability.

There is always hope, of course. Floyd Mayweather Jr., won 49 fights and probably took no more than seven or eight damaging shots over that entire period. George Foreman was heavyweight champion of the world over two different eras, which involved many punches taken and a knockout by Muhammad Ali. Yet, you cannot find a sharper, more lucid human.

Still, the norm is not pretty. I once interviewed the widow of boxer Mike Quarry days after this death. She told stories of changing his diapers and chasing him around the neighborhood when he wandered off.

In a recent article on the website The News Outlet, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons calculated that 90% of boxers end up with some sort of brain injury. That runs neck and neck statistically with the recent work on NFL brain injuries, where the Boston University Center for the Study of CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy) recently announced that, of the 91 brains it has studied, 87 had CTE.

I worry about Bradley because his wife does.

I worry about Pacquiao, because he has already taken a huge knockout shot from Juan Manuel Marquez and because, if he can overcome his silly recent statement about gays and lesbians, he may become a Philippine senator, where they will need a man with all his faculties.

I worry about Pacquiao’s trainer, Freddie Roach, who is a great guy and former boxer turned world-class trainer, but whose limp seems to worsen and speech seems increasingly blurred.

But they all knew. They signed on for the shot at glory with full knowledge that it might bring them only brain damage. Boxing is brutal and they all knew that going in.

Football is the same. Brutal. But until recent years, when science simply forced itself on the see-no-evil, hear-no-evil NFL, football players did not enter battle pondering the possibility of lifetime scars.

They didn’t know. Jon Arnett didn’t know. Nor did Conrad Dobler, Tony Dorsett, Todd Marinovich, Bob Lilly or Alex Karras. Nor did my Notre Dame classmate, the late Pete Duranko. They played with illusions of grandeur and visions of sugar plums, while the NFL led them along, like lambs to the slaughter.

A Texas law firm hoping to represent many of the thousands involved in ongoing litigation against the NFL for all of the above and thousands more, O’Hanlon, McCollom & Demerath, lays out the case of action in the simplest of ways:

“Although the medical community was informed by evidence from other sports like boxing and had understood that repeated impact to the head can cause long-term brain damage for decades, the National Football League ignored the medical risks and sent players back onto the field, often in the same game.”

Both sports are violent. But boxing’s participants were always aware of that and chose it with full knowledge. Until recently, NFL’s participants were conned into risking life and limb. Their career decisions were made without knowing everything about their career.

It’s not all right if a sport is mostly violent, but it is less odorous if it never hides that.

The NFL, in the category of brain injuries, has left a stink for years to come.

That’s my rationale. Write me an email and that’s how I will respond.